Breaking Free of the Classroom: Field Work in Forests

The call of cicadas rings through the blue pine dominated forest. Under our feet, the ground is soft with decaying plant matter and bamboo shoots grow as grass does back in the US. Right in front of me, slowly being swallowed by the vegetation, is an old truck tire, and off to my sides are scattered backpacks and a pile of water bottles. From the top of the hill, I hear my name being called: “Renne, does your group have the pH probe?”

The morning had begun with a quick breakfast and preparations to leave on our forest inventory Field Exercise, also known as a FEX. As we left the field center, each student made sure he or she was “looking FEX-y” with hiking boots on her feet and notebook, water bottle, notebook, lunch, and raingear in her backpack. The hour-long bus ride to the community forest took us through town and past the rice paddies, and then ascended to the community forest via a windy road lined with prayer flags.

Once at the community forest, our professor, Dr. Purna, gave us a reminder of the importance of community forestry in Bhutan. During a lecture the day before, we had learned that the first community forest in Bhutan was established in 1995 to give people ownership of and access to their own forests, and now there are almost 700 community forests in the country. The biggest hindrance towards establishing more community forests is the requirement that community members put together a plan that establishes the current conditions of the forest and sets guidelines for sustainable use, such as how many trees can be cut per year. The work we would be doing in our forest inventories is representative of the requirement to establish current forest conditions.

Dr. Purna then gave us quick demonstration of how to collect data on land use, trees, and other vegetation, and we were introduced to a government forester who taught us to core the trees. Then we split into groups and were off! My group was assigned to work in a low area, next to a meadow. We made our way down the steep hill, avoiding anything with thorns (everything here seems to have them) and trying not to slide on our butts. At the bottom, we found a large truck tire and designated it as the center of our plot. In each of the four cardinal directions we measured outward 13m and marked the spots with our backpacks. This formed the outer limit of our circular plot. Then we started our data collection. We noted land use, like cow tracks in the dirt, the truck tire, and the presence of pollinators. Soon after that we designated five 1x1m subplots, marked the corners with our water bottles, and counted the vegetation. We had 25 plant species within just our plot! Our professors aren’t kidding when they say biodiversity is high!

Partway through the day, our group took a break for lunch and the tire served as the perfect seat for all six of us. After lunch the exciting part of the project began: collecting data on the trees. Working clockwise, we gave each tree in our plot a hug as we attempted to measure its circumference. Then, using three different methods (each requiring different amounts of math), we calculated the height of every tree. Finally, we picked the two biggest trees in our plot to core and took turns screwing the borer into the trees and listening to the creaks that echoed through the woods. Back in our classroom that afternoon, we mounted and sanded our cores, and then practiced telling the story of the trees, incorporating both changes in the environment and important dates for the country and the world.

As an anthropology major, I had always assumed that forestry was technical and, albeit important for grazing and timbering regulations, minimally applicable to broader issues of social importance. Looking at forestry through the lens of small-scale social forestry, rather than large-scale operations, brings concepts of equity, livelihoods, and development to the forefront of our learning. We are forced to ask, for example, what effects does access to and use of forest resources have on the local community and on global processes? This line of thinking is not unique to only the forest inventory FEX. Within the last couple weeks, we’ve also mapped land use around town, kick seined for invertebrates in the river, visited a traditional medicine hospital, and much more, all of which were interdisciplinary learning experiences that illustrated the interconnectivity between the social and natural sciences. New knowledge is at the base of every mountain here in Bhutan, and FEXs are the perfect way to break free of the classroom and explore.

Lucia, Annie, Zach, and Renne pose with an increment borer used to pull core samples from trees in order to determine their age. This practice is widely used in the science of dendrochronology

Finley and Annie work together to measure and record the diameter of a tree within their study site

Land Use and Natural Resource Conservation professor, Dr. Purna Chhetri, conducts a field lecture during one of the group’s outings. Photo courtesy of Greg Francois

Related Posts

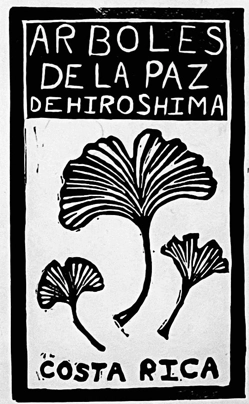

Trees of Peace from Hiroshima: A Time Traveler and Emissary of Hope

Cinder Cone Chronicles: Lessons from Drought, Data, and Determination