By: Sigrid Heise-Pavlov, PhD

Cinder Cone Chronicles: Lessons from Drought, Data, and Determination

The story of restoring a Mabi-type rainforest on a steep volcanic cinder cone continues—with new insights, tough lessons, and resilient optimism. Since our last update, we’ve endured a long dry season, collected exciting experimental data, and uncovered critical findings that will shape the next phase of our syntropic restoration journey.

A Harsh Reality Sets In

By late September 2024, signs of seedling stress became undeniable. Our exposed restoration site—devoid of the natural shade provided by mature trees—offered little refuge from the searing sun and deepening drought. With no rain from early October through November, many seedlings began drying out, and urgent action was required.

Photos 1 & 2 (above): showing drought-affected seedlings; Photos 3 & 4 (below): CRS staff watering seedlings during the Dry season of 2024

We mobilized quickly: irrigation lines were adapted to water four plots at once, mulch was temporarily shifted to allow water to reach the roots, then carefully replaced around each seedling to retain moisture, and each seedling received three liters of precious water. What followed were exhausting early morning and late-night watering shifts—sometimes stretching past 11 p.m.—under the beam of headlamps and the distant hum of sugarcane harvesters. We had shifted to night watering simply because it had become too hot during the day—for both people and plants. Midday evaporation was intense, and even the water itself warmed up before reaching the roots, reducing its effectiveness.

Data-Driven Discoveries

Amid the challenges, two student researchers conducted the first monitoring of our April 2024 planting. Their findings have given us new perspective on which species are best suited for this unique landscape:

Survival Winners and Losers

The standout survivor was Syzygium australe (Lillypilly) with an 86.11% survival rate, followed by Neolitsea brassii at 83.33%. In contrast, Castanospermum australe (Black Bean) fared poorly, with only 55.55% surviving.

| Species | Survival Rate |

| Alstonia scholaris | 77.77 |

| Castanospora alphandii | 75 |

| Castanospermum australe | 55.55 |

| Pleioluma papyracea | 77.77 |

| Syzygium australe | 86.11 |

| Darlingia darlingiana | 80.55 |

| Euroschinus falcatus | 77.77 |

| Ficus henneana | 72.22 |

| Neolitsea brassii | 83.33 |

Table 1. List of species planted on the cinder cone and their survival rates between April 2024 and November 2024.

Banana Companions Under Scrutiny

Our experiment with bananas as nurse plants revealed they may not be suitable for such dry, sloped terrain. Survival was low (only 8–24% across plots), likely due to their high water demand and the cone’s rapid runoff.

| Plot | Number of Living Banana Plants | Percent Survival of 25 Bananas Planted |

| A | 2 | 8% |

| C | 6 | 24% |

| F | 4 | 16% |

| H | 4 | 16% |

Table 2. Number of banana plants and their survival rate in each banana-containing plot.

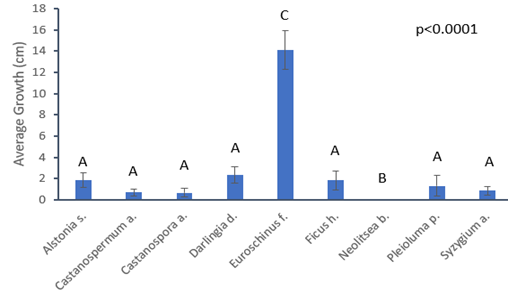

Growth Trends

While Neolitsea brassii showed little growth, Euroschinus falcatus thrived. Each species is teaching us more about resilience and adaptability in this extreme environment.

Table 2. Number of banana plants and their survival rate in each banana-containing plot.

Soil Moisture Matters

As suspected, soil on the cinder cone had 32.2% less moisture than mature Mabi forest soils—an enormous hurdle for young plants.

After the Rains, Another Challenge

Rain finally arrived in December, breathing life back into many seedlings. Even some that looked like dry sticks began to leaf out again. But just as quickly, a new issue emerged: the weeds surged. Seedlings were soon buried under human-height pasture grass. The labor to rescue them was intense. Staff spent hours crawling through dense undergrowth to find and clear seedlings. Eventually, with the landowner’s consent, we applied a grass-specific herbicide—carefully and sparingly—with help from Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. It was a turning point: finally, we could see the seedlings again.

The Wet 2025 Season: Intense Rains, Fast Growth, and Fierce Weeds

The Wet 2025 season delivered exactly what seedlings needed—heavy and consistent rainfall punctuated by occasional sunshine. Many previously stressed seedlings responded immediately, flushing out new growth. But with the rains came a surge in weeds, particularly vines like glycine and herbs like Bluetop, which thrived after the grass was suppressed by an earlier herbicide treatment.

Fortunately, students arriving at the start of February jumped into action. Staff had pre-marked each seedling with pink tape to help identify them among the dense, dead grass and regrowth. Students methodically cleared vegetation by hand around each seedling, accelerating their access to sunlight and space. Their work made a measurable difference—growth was visible within days on many seedlings.

The season also brought a major logistical milestone. A permanent fence was installed along the lower boundary of the 2024 planting site using 40kg concrete posts and quick-set cement, a labor-intensive effort shared by staff and students. This fence allowed cattle to continue grazing below the 2024 planting area while protecting new planting zones above. With support from TREAT, the local tree-planting NGO, augers were fitted with deep-drilling extensions to complete the installation quickly. A wildlife-friendly top wire without barbs capped the project.

By March, the electric fence was relocated uphill to enclose the upcoming 2025 planting area. The rainy season, while demanding in labor and coordination, was ultimately a period of recovery and advancement for the project. Every step reinforced the collaborative, adaptive nature of this initiative—and how vital the timing and intensity of seasonal rains are for rainforest regeneration on the cone.

Growing Smarter: The 2025 Approach

Our experiences over the past year—and especially the lessons drawn from the 2024 planting—have deeply shaped our strategy for 2025.

To begin, we’ve refined how we prepare the site. One key insight was allowing cattle to graze the new planting area right up until a week before planting. This helped suppress grass growth and dramatically reduced the labor needed for pre-planting grass removal.

Species selection has also evolved. Poor performers like Black Bean were removed from this year’s planting mix, replaced by hardier Mabi rainforest species, including new additions such as Eleocarpus grandis, Flindersia schottiana, and Cardwellia sublimis. Each of the eight new plots features nine different species with four seedlings per species, following the same structure as 2024 but with a revised species list tailored to the cone’s tough conditions.

We’ve also adapted our approach to companion planting. Based on last year’s low banana survival rates, bananas were replaced by Homalanthus novoguineensis (Bleeding Heart), a fast-growing pioneer species expected to offer better shade and support for the seedlings.

Site preparation began in March with intensive lantana removal—an invasive shrub avoided by cattle that had taken over parts of the paddock. By early April, with fencing in place, students and staff measured plots, drilled holes, and added water crystals and fertilizer.

On April 12th, 28 students and 6 staff successfully planted 288 seedlings. This time, seedlings were watered into the ground—a first for the project—thanks to improved water access via dual 1000-liter water pods installed just below the planting zone.

After planting, cardboard was placed around each seedling to conserve moisture, and one week later, a grass-specific herbicide was applied to manage early weed competition. These steps reflect our growing toolkit of restoration strategies—each informed by data, observation, and experience.

Looking Ahead

As we enter the dry season, we’ll be closely monitoring the 2025 planting to see how this new generation of seedlings responds. Each phase of this project teaches us more about what it takes to bring rainforest life back to the cone. With every root in the ground and every adjustment made, we edge closer to building a restoration model for even the harshest environments.

Restoring a rainforest on a steep volcanic slope—with no existing blueprint—demands grit, adaptability, and collective effort. To our partners and donors: thank you for helping us grow both knowledge and forests, seedling by seedling.

To further support the cinder cone project, please consider making a donation.

Related Posts

Trees of Peace from Hiroshima: A Time Traveler and Emissary of Hope

Cinder Cone Chronicles: Lessons from Drought, Data, and Determination