Culture-Conscious Conservation in the Amazon

As I tilt my head back and gaze up at the Milky Way stretching over the Yarapa River, I think about everything that I’ve seen today. The morning began with a hike where we followed ocelot tracks and called to capuchin monkeys. On the boat ride back to the research base, we encountered a three-toed sloth swimming VERY slowly across the river, his grinning face bobbing up and down with each slow-motion stroke. Later we counted shore-birds including kingfishers, terns, egrets, and even the hilariously awkward horned screamers. During the ride we were able to see squirrel monkeys hopping from tree to tree and pink river dolphins circling the river mouth, searching for fish. Now we are cruising in an open wooden boat under the stars, using a spotlight to search for caimans along the rainforest shore. To be able to encounter all of these animals in such a short time seems unreal, but this was no day out of the ordinary in the Amazon. The energy contained in this place is indescribably vibrant and the forest constantly spills over with sound and movement.

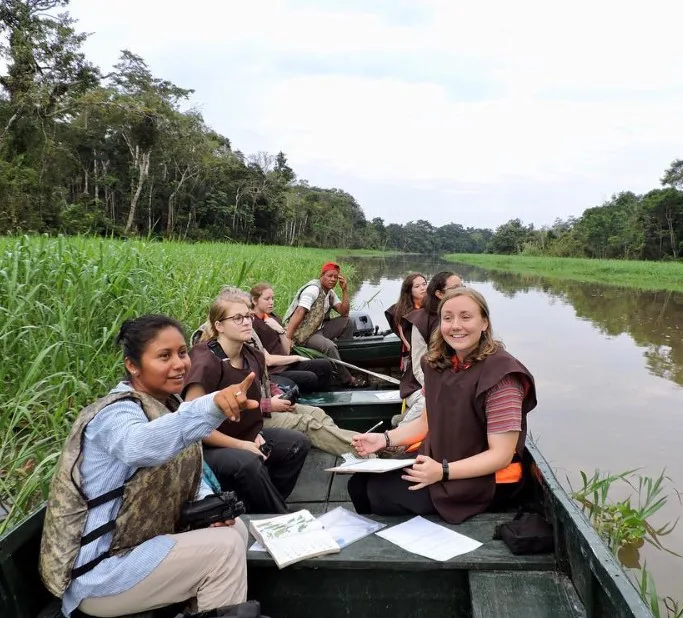

Photo courtesy of Emily Wayne

This area of the Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo National Reserve was not always so lively and diverse. During the 1940s, outsiders began to invade the area in order to harvest and exploit the rubber trees that grew there. Throughout the 1900s trees were clear-cut for timber and animals were hunted nearly to extinction for pelts and the exotic pet trade. The indigenous people living in the area lost their usual food sources and areas of forest that had traditionally been used for sustenance hunting for generations. As the forest was continually degraded, they lost more and more access to the natural resources that they had always been dependent on. In the 80s, they reached out to a team of scientists who were coming to the area to study animal populations for help. Together, with the Peruvian government, they created a regional conservation plan that was revolutionary for the Amazon.

Photo courtesy of Emily Wayne

When Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo was named a national reserve, emphasis was put on allowing the sustainable use of resources by the indigenous communities already present in the area. Community members were allowed to continue fishing and hunting and using rainforest resources while teams of conservationists monitored the processes to make sure that they were being done sustainably. Outsiders were kept from invading and over-exploiting the resources and the forest began to heal. Monitoring work continues today in order to measure the health and diversity of the area. We were able to count bats, dolphins, shore-birds and catch fish along the Yarapa to assess the fish populations. Macaws were counted to reveal fruit presence, while land mammals and caiman numbers gave us information about local hunting. Through this mutualistic conservation process, local communities have been able to restore their former levels of resource access while the forest has been able to recover and replenish endangered animal populations.

Photo courtesy of Emily Wayne

Being able to both take conservation data along transects and interact with the local communities in the Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo reserve made the visit an eye-opening experience for me. As a science student, many of my classes are solely focused on the empirical side of conservation, forgetting that local people are often dependent on local resources and that ignoring their needs and rights in an effort to “save” an area can end up causing more harm than good. This reserve is a dynamic example of a model in which through cooperation between scientists, local groups, and a little bit of governmental help, higher levels of conservation and biodiversity can be reached. Seeing this kind of success in a protected area gives me so much hope for our natural world’s future and makes me excited to continue learning and, hopefully, eventually be a part of similar conservation work.

Related Posts

Restoration on a Cinder Cone: A Syntropic Story