By: Luke Stover

Friction, Balance, and Reflection

During the sun-lit hours of breakfast and lunch, we are treated with la vista: the (grand) view from our tables in the kitchen. The amount of space that our eyes so fluidly navigate to reach the trees below and the mountains in the distance must characterize any vista. Being so, I try to be cognizant of the life that occupies the space in between; my eyes often focus on the birds flying throughout the valley and their wingspans that allow them to soar with ease.

Yesterday, from a hammock I watched one of these birds struggle to stay aflight as it fought wind. The friction of the wind against its body prohibited forward motion and for an instant, the moment was frozen. The loose piece on the porch roof rhythmically whapped against its secured counterpart, the leaves on the trees clashed against one another. The bird held its place until shifting to a plane one meter below in the sky and disappearing from sight, escaping the friction.

We take ourselves to be frozen in time, static beings displaced only by sudden shifts. We forget that we are always moving forward, always being constituted and reconstituted, always stepping into a future that is both like and unlike anything we have encountered before. Things are constantly being configured, assembled, and reproduced; generating friction which propels us forward. How do we represent ourselves in a way that honors the experiences of friction that have shaped our pasts? (When Friction Starts and Stops: A Historical Auto-Ethnography. Reinert 2019.)

In an endeavor to faithfully honor these experiences, I consider the difference between the verb “to reflect” and the noun “reflection” (what I see when I look in the mirror). I know for certain what the later is: a direct, physical replication of what’s placed right in front of the mirror. Now let’s add some human nature into that visual translation, acknowledging our capacity to make judgments on that reflection. For example, I can recall looking at myself in the mirror during the long days of Directed Research, seeing bug-bitten arms, hair that has had its volume sucked away from the hat that had been pressed on my head, and rubber boots dirtied by creek-mud. All tell the story of our trudge through the Quebrada Matías, which is a deeper inspection than only seeing the physical being. Now, just as we added human nature, prepare to introduce the factor of time and to capitalize on the restriction of light’s speed. Know that after the light travels from you to the mirror and to your eyes, a fraction of a millisecond has passed the reflection you see lives in the past. Uday Chandra and Atreyee Majumder describe the self processually, as a being that is constantly dynamic. They write that “the making and remaking of the ‘self’ is an ongoing process, and what we observe before us at present ought to be understood as no more than a fleeting glimpse of an object in motion”.

The differentiation gap between the verb and noun of “reflection” shrinks, and now I’ll merge the two through a visualization: A clear pool of water at my feet, I look down and I see my reflection. If I look down for too long and reflect too much, I risk trading off experiences I could be having in that moment. But if I don’t look down at my reflection and choose to ignore it, I know that pool will shrink as my memory fades with the passing time.

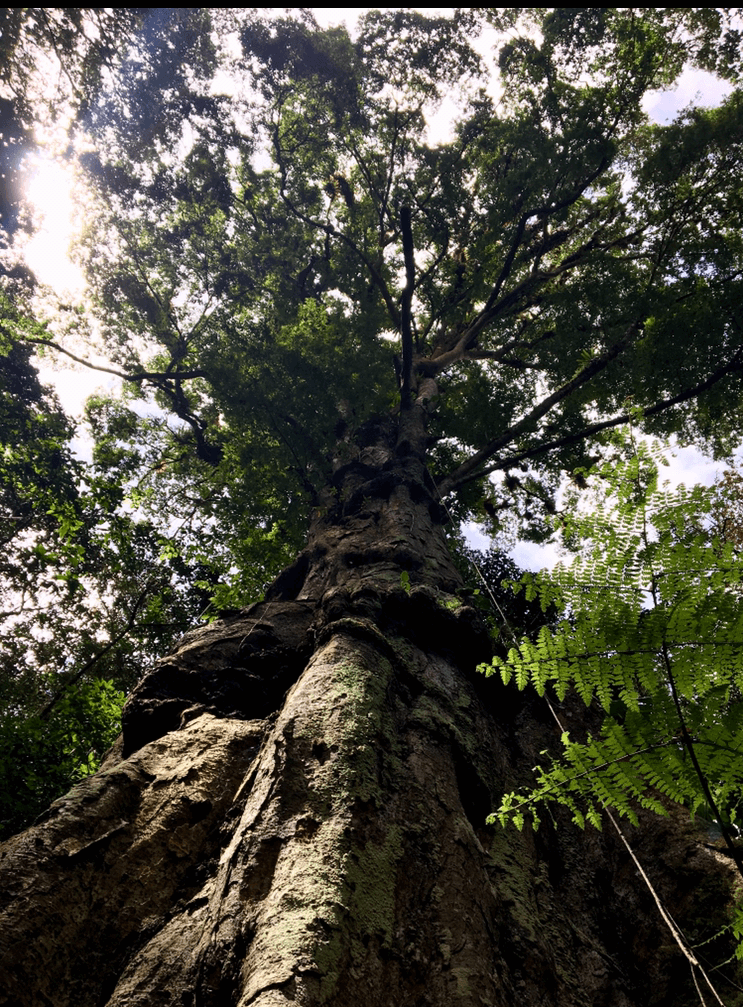

In this junction, I challenge myself to find my balance: Practice introspection but don’t dwell; smile in the moment that the morning sun shines through the tall canopy, and sings out on the walk to breakfast; notice the subtle indicators that time is passing within yourself and your environment. I feel grateful that Atenas has given me comfort within friction.

Related Posts

Camila Rojas: Alumni Spotlight⭐