By: Arden Simone

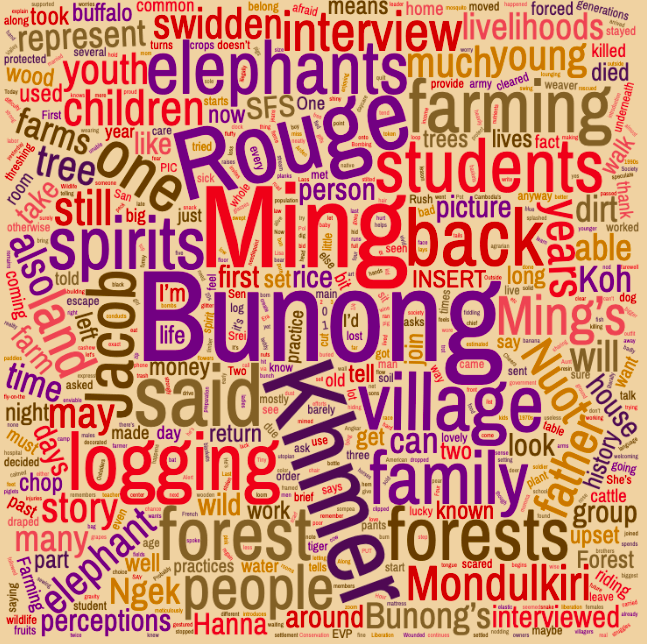

Histories of the Bunong Indigenous People

This month, SFS students are focused on Directed Research (DR) — one of my favorite parts of the semester. I enjoy DR because it is applied, experiential, purposeful, project-based and “real world experience” learning, and it grants students agency and autonomy.

This semester for DR, eight of our students are based in Siem Reap studying 1) bat behavior, 2) dog welfare, 3) solid waste management, and 4) merit release practices. Four other students are based in Sen Monorom, Mondulkiri, studying 1) natural resource use, 2) youth livelihoods and perceptions of logging, and 3) village histories. I’m currently with the group of students in Sen Monorom, and I’m enjoying learning about the Bunong people alongside the students.

First off, I’d like to provide a brief description of the Bunong. As with most descriptions about a group of people, it’s generalized, simplified and distilled; therefore (among a million other factors), is inherently incapable of doing justice to a group of diverse individuals like the Bunong. This brief summary touches upon the cultural distinctness of the Bunong, their belief in spirits, their connection to elephants, their weaving practices, and their livelihoods.

The Bunong are an Indigenous group who live in the highlands of Cambodia, usually in Mondulkiri Province. They tend to be culturally distinct from the Khmer (the majority group in Cambodia) although this cultural distinction is decreasing over time due to various factors. These factors include the “Khmerization” of the Bunong during King Sihanouk’s political period (particularly between 1954 and 1970), the gradual diaspora of young Bunong, the migration of lowland Khmer into Bunong Villages, and of course, the ever-present introduction of technology and media.

2) Central to the Bunong’s lives are their traditional beliefs in spirits. Today, there are also many Christian and Buddhist Bunong. Bunong that believe in spirits believe that nature is populated by spirits that must be respected and appeased. For a beautiful depiction of the spirits in forests, take a close look at the following painting titled “Alert in the Village!”, painted by Hour Seyha, a Khmer (notably not Bunong) artist.

Over the past couple days, several villagers have talked about logging and deforestation in relation to spirits. One woman said that if someone would like to chop down a tree, he or she should go to the forest and ask the spirits if they can chop down the tree. Then, the person should return home, and that night as the person sleeps, the spirits will tell them whether or not they can chop down the tree. If the spirits say yes, the person can go back to chop down the tree. However, if the spirits say no but the person still chops down the tree, the spirits may cause bad things such as illnesses or big storms. Notably, there are entire spirit forests that the villagers feel adamantly should not be cut down.

3) The Bunong also have a strong connection to elephants. Before the Khmer Rouge, most Bunong villages had multiple elephants used for transport, heavy labor, and more. The elephants were treated with great respect. During the Khmer Rouge, the Bunong elephants were largely stolen, killed, sold, or otherwise lost. After the Khmer Rouge, not only did the Bunong loose their elephants, it was also made illegal (in the 1990s) to capture wild elephants.

SFS students have the opportunity to learn about elephants and the Bunong’s connections to elephants first hand while visiting Elephant Valley Project (EVP) in Mondulkiri. Here students go hiking through forests in pursuit of roaming elephants, and speak with the Mahots — the Bunong people who take care of the elephants at EVP.

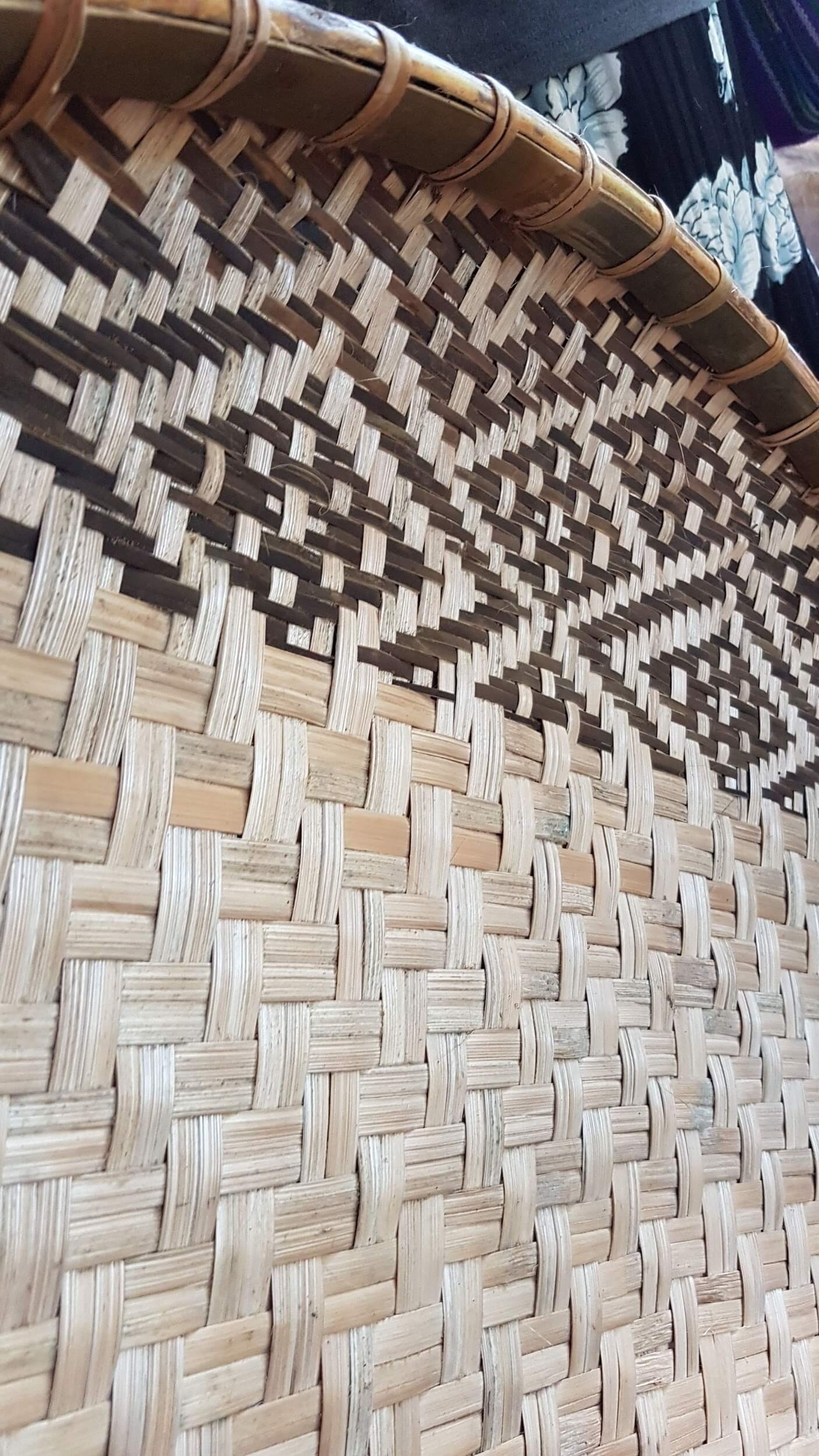

4) The Bunong are also known for their traditional weaving of textiles and baskets. Last semester, we met a Bunong man who showed us a beautiful threshing basket (used for rice preparation) that he had woven. He was upset to tell us that none of his children learned how to make this pattern and he is afraid that nobody else knows this pattern either. He worried that this traditional pattern will be lost forever.

This lovely man was very excited when some of our students asked to take a picture of his weaving and a picture with him. Here is a picture of me with him and the threshing basket, as well as a close-up of his fine work.

Moreover, the Bunong are known for traditionally weaving gorgeous textiles. These textiles include Kramas (scarves), blankets, clothes, and much more — mostly done on a tiny loom that you must loop over your feet and pull taught (see pictures below). According to Mondulkiri Indigenous People’s Association for Development, each Korm (design) on the textiles represent an important part of Bunong Culture. For example, the “Arrow and Kaisna represent the hunting of Bunong. The python, the snake image, the nose of tiger image, and the great silver water beetle image represent fierce wildlife. The images of guord, cucumber, pumpkin, and rice represent the planting of crops. The images of a waterfall, wildlife, stream, mountain, and water represent the livelihood landscape of the Bunong. Rabbits represent wise and intelligent people”. This list goes on. Today, most Bunong can be seen sporting more “modern” clothing — for example a pear of jeans or comfortable elastic pants with a T-shirt or zip up jacket.

This semester, we were lucky enough to meet a Bunong weaver and take a lesson from her. Here is a picture of the weaver and I with the scarf I bought from her draped over our shoulders!

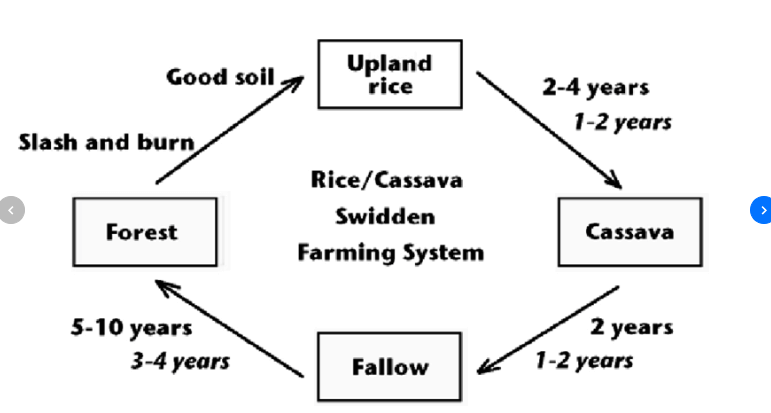

5) As for the Bunong’s livelihoods, the Bunong are traditionally swidden farmers. They also traditionally rely on Non-timber Forest Products.

Swidden farming, otherwise known as shifting cultivation, is a “nomadic”style of farming. Swidden farming means that they 1) clear and burn forests to plant farms, 2) grow crops on that farm for several years 3) after several years — when the soil loses its nutrients — leave that farm for another, and start all over again… back to step 1! Eventually, swidden farmers return to their previous farms after years of regeneration and regrowth.

Relevant to swidden farming (and Bunong culture as a whole), the Bunong believe that forests belong to everyone. “Back in the day” in Mondulkiri, swidden farming worked because farms were plentiful, shared, and there for the Bunong to use. Within the last 20+ years, this has changed.

Flash-forward to today, and despite the fact that the Bunong may still believe that forests belong to everyone, that concept is no longer seen in practice. Mondulkiri is now a quilt of privately owned land demarcated by fences and stakes. It’s defined by land concessions, people selling their land to avoid poverty, and more. This prohibits the Bunong from moving about as needed for their swidden farming.

The Bunong supplement their farming practices by collecting non-timber forest products (NTFP). These products include vegetables, fruits, honey, herbs, fish, animals (small deer, wild pigs, etc), traditional medicine, resin, and more. SFS students Karlie and Brynn are doing their directed research on NTFPs.

However, now that the Bunong are losing their land and forests that once “belonged to everyone” to private landowners who are often clearing/leveling the land to plant homogenous farms, they barely have any forests left to look for NTFP. According to mongabay.com, “Cambodia lost around 1.59 million hectares of tree cover between 2001 and 2014 (that’s the size of Connecticut!), and just 3 percent remains covered in primary forest.”

In interviews, many villagers have said that there are barely any animals left in the woods, let alone honey or fruit or vegetables. In Karlie and Brynn’s findings, they “have noted that across the board, there is a general trend of less access and availability of NTFPs, particularly of wild vegetables, wild fruits, and wild mushrooms” ~ Karlie/Brynn/paraphrased by Arden

So why are these forests being cleared? There are two main factors (and SO many more!):

1) Outsiders (Khmer, vietnamese, chinese, big corporations) are now coming into the Mondulkiri region for the sole purpose of logging and selling the wood. You can make big bucks selling “special wood”, aka hardwood such as rosewood. Many interviewees have said that there is no “special wood” left in the forests. With all of the big corporations and outsiders coming into the Bunong’s land, some Bunong have taken up logging as well, thinking “if my land is going to be cleared anyway (to my community’s detriment), I may as well be the one to profit from it”.

2) “According to the young men who were interviewed, logging is very common among youth in the village. Nearly every interviewee mentions that the main reason that the logging is occurring is due to the fact that they need money. The youth feel that farming no longer provides enough income or food for them to survive throughout the year, so they log the forest in order to provide for themselves and their families. The young women who were interviewed also agreed with the fact that many poor families are resorting to illegal logging in order to make enough money to survive. Interestingly, although the youth log the forest, they still perceive that cutting down the trees will have negative consequences. Every young person that has been interviewed has explained that when trees are cut down, climate change will be much worse and there will be many problems for future generations.” ~ Hanna Rush

With this brief, generalized and likely flawed overview on the Bunong established, I’d love to introduce you to a lovely Bunong woman that I had the pleasure of talking with twice over the past two days. Out of the necessity of anonymity, let’s call her Ming. That means “Aunt” in Khmer, and is a common and respectful way to address a woman of her age (53 years old).

On Monday, Hanna interviewed Ming’s impressive children for part of her DR studying youth livelihoods and perceptions of logging. During this interview, Hanna aimed to interview Ming’s children (Hanna’s research on youth perceptions requires that her interviewees be under the age of 25) but Ming kept answering our questions anyway. She eager to talk to us about her opinions of logging, the environment, and much more. The interview lasted about 2 hours.

The next day, I returned with Jacob, the SFS student studying Bunong history. This time, we were there to talk to Ming, and Ming only!

Her story was nothing short of jaw-dropping.

Please note that when I write about Ming’s interview, sentences may be choppy or short. I didn’t want to add anything to Ming’s story in fear that it may be speculation or untrue. Given Ming’s gestures and long dialogue, I’m sure she painted a vivid picture of this story. That being said, after translation, this is most of what I gathered:

I sit around a heavy, lacquer-polished table that looked a lot like it was made from “special wood”. To my right sit Jacob and Nuot, our Bunong translator.

Within 30 seconds of us sitting down the first time we met Ming, she told us that she got this table from another village. Within a few more minutes, she tells us how much she cares about protecting the forest — and she really means it.

When Jacob and I meet Ming, she wears a pink button up shirt and a patterned sarong — the same outfit she wore at yesterday’s interview. I’m also wearing the same exact thing. She has long shiny black hair clipped in an enviable bun on her head. She makes sure that the three of us (Jacob, myself, and Nuot) all have a bottle of water and a snack of banana and grapes.

As Nuot introduces us to Ming in his native Bunong tongue, I look around the house.

Ming’s stilted house is made out of wooden planks, is meticulously clean, and is decorated with painstakingly-done needlepointing art. One needlepoint is of horses running through a forest and another is of flowers, a teddy bear and two glasses of wine with a clock. Both are splashed with glitter and framed.

From my chair I can see into two different rooms. In one room two old ladies are lounging underneath a mosquito net. In another room, one of her sons who we interviewed yesterday lays on a blue floor mattress fiddling with his smart phone. Throughout the interview, family members flow in and out of the house.

The interview begins, and Ming invites us into a bit of her history and life.

She says she’s lived in this village for her whole life. She’s a farmer. She used to farm rice, but now she farms cashew nuts and raises 3 buffalo and 15 cattle. She used to have many more cattle, but she had to sell them to buy the timber for building the house. When her husband was alive, she lived in a different town and he supported her; but when he died she moved in with her younger brother into her current town and helps him farm.

Jacob asks Ming a bunch of questions about history — the French period (1867 – 1953), and King Sihanouk’s Era (1953 – 1970). Ming says she doesn’t know too much about this because she was not born yet or too young to remember. Then, we get to the Khmer Rouge, the government (otherwise known as Angkar) that killed an estimated 2 million people (1/4 of Cambodia’s population) between 1975- 1979 in efforts to create a “pure utopian agrarian society”. Then, Ming has a lot to say.

First off, Ming remembers American Bombing. She said she was only 2 or 3 when it happened, and that she had been hiding with other children at the farms from the bombs. She said that a bomb dropped on her farm and the soil that was kicked up from the bomb buried her baby brother. Luckily, her brother was able to get out from underneath the dirt, which we were told by Nuot, our translator, as he mimed to us her brother trying to dig himself out of the dirt.

Jacob asks her “ When did the Khmer Rouge first start coming to your village? What did they tell people? What did they do?”

Ming starts talking for about 15 minutes straight, which she does many times throughout the interview. She’s amazingly talkative! Of course I can’t understand what she’s saying, but Jacob and I nod along to her story when seems appropriate. I worry about how much we are missing when Nuot tries to translate this to us; but regardless, we don’t want to interrupt her.

I look outside. Ming’s dirt yard is swept neatly — there’s not a bit of trash or kicked up dust on the dirt. Out on the road, motorbikes with 4+ people squeezed on zoom by. A fluffy dog saunters around. He’s a funny copper orange color from the dirt he’s surely been napping in. Adorable little piglets with wiggling tails trot in the front yard, followed by their giant momma pig (described as the opposite of a glow-up by our students). A few chickens peck at the grass, and a grazing cow tries relentlessly to eat a plastic bag that’s strewn on the ground.

When Nuot is able to translate, he tells us that when Pol Pot’ (the leader of the Khmer Rouge) soldiers came to Ming’s village, her parents “weren’t comfortable with them”. The Khmer Rouge set up “education” to get people to join the Khmer Rouge. She and her family didn’t want to join the Khmer Rouge, so they decided to try to escape. She explains how they left in the middle of the night and fled to Vietnam. They walked at night, and during the day they hid in the forest behind trees. She was just a little girl (about 7?) and told us that she was very sleepy as she walked.

When Ming and her family got to Vietnam, they were protected by Vietnamese military and they started farming rice. After one year, her family falsely assumed that everything had “gone back to normal” in Cambodia and decided to return. In reality, the Khmer Rouge Genocide was in full swing. When Ming and her family returned to their village they found the Khmer Rouge still occupying, and still “educating” people to join their army. Ming said that her family had no choice but to join the Khmer Rouge. After joining the Khmer Rouge, Ming and her family were relocated to Srei Ambom. There, in this resettlement village, her mom and siblings stayed in the village while her father was forced to transport goods for the Khmer Rouge via an elephant.

About 3 months after her family moved to Srei Ambom, her father was out transporting goods, when one day the elephant that he was riding on top of encountered buffalos that were upset from being hit by their owners. The buffalos scared the elephant that her father was riding, and sent the elephant running into the forest with Ming’s father. The elephant ran very far, and when it stopped, it was still very scared. Her father tried tying the elephant to the tree so that he could return to the village and come back when the elephant had calmed down. However, when he did so, the elephant, still upset, attacked her father and hurt him very badly — Ming gestured to her arms when she said this. Wounded, her father tried to walk back. When he returned, the Khmer Rouge took her father to the hospital, where he died from his injuries a few days later.

Ming says all of this with such a straight face that Jacob and I, nodding along, having no idea what she’s saying, and waiting for the translation, have no idea the gravity or difficulty of the story that she is telling us.

Ming continues. After her father passed away, her family was relocated again to Koh Ngek. She and her family were among the first to be relocated. The Khmer Rouge relocated them because they were afraid that they would escape to Vietnam again. Ming said that it took them five days to walk to Koh Ngek. Along the way, they took turns riding elephants to rest their legs.

In Koh Ngek, Ming said that there were not too many Bunong, mostly people from Laos. In Koh Ngek, Ming was sent to work at a daycare to take care of other small children (even though she was still very young — maybe 8 or 9?). During this time, her mother was forced to work in the fields making rice paddies. Ming said that her mother worked very hard, and that if they didn’t work, they would be killed.

Ming stayed in this Khmer Rouge settlement for 7-8 long years. In the late 1970s, she was freed by the Vietnamese Liberation. She said that she was very lucky that they were rescued when they were, because the Khmer Rouge was planning on killing everyone in the resettlement camp except for “10 males and 10 females of each race”.

Jacob then asked, “After the Vietnamese liberation, where did you go?”

Ming proceeded to explain that she began to walk back to San Monorom (a bigger town about 30 minutes drive from Oreang, where she currently lives) from Koh Ngek. All she carried back with her/ had after about 8 years of being in Koh Ngek was able to fit into a basket. She was also able to bring back one buffalo.

She said that it took a long time to walk back, and that as she walked she was attacked by the Khmer Rouge. What seemed particularly disturbing to her was that she was attacked by “brothers”, people she knew, who had joined the Khmer Rouge. Luckily, she says, the Vietnamese protected her and the other villagers who she walked with.

When Ming arrived in San Monorom, she settled there, married her husband and set up her life. When her husband died, she went back to her home village to live with her brother, and began practicing swidden farming. This was in 2000, about 30 years after she was first forced out of her village by the Khmer Rouge.

Nowadays, Ming spends her days farming. Her biggest struggles today seem to revolve around the deforestation nearby her village. She worries that all her land is disappearing and she doesn’t know how they will regain this loss. For Ming, this deforestation means a lack of livelihood opportunities, upset spirits, and “a sense of powerlessness”.

Ming feels very strongly that she wants her children to complete education so that they may have better lives. She must be incredibly proud of her children, all of whom have already graduated from university or are currently enrolled. One of her children was in law school, one a teacher, one an army soldier, and one working for Wildlife Conservation Society to protect the forest.

Two hours later, we bid our farewell to Ming. We ask Nuot to tell Ming again that this research and her story will be given back to her community chief. We give some tiger balm and toothpaste (“thank you gifts”) to Ming, which are a mere token of our immense gratitude toward her, we say thank you a million times, and, folding our hands in sompea with one last “thank you so much!” from Jacob and I, we set off down the road to meet someone else.

I’d like to express my gratitude to “Ming” for sharing her story with us, to her family for welcoming us into their home, to Nuot for somehow being able to translate 20 straight minutes of dialogue at a time to us, to Hanna and Jacob for letting me be a fly-on-the wall while they conduct interviews, and to Lisa for setting up and supervising this research.

— Arden Simone

SOURCES:

https://www.cambodiadaily.com/news/how-late-king-norodom-sihanouk-brought-french-rule-to-a-peaceful-end-46825/

https://www.mondulkiriproject.org/bunong/

https://www.sil.org/system/files/reapdata/10/25/05/102505256102132918784371836523283484815/ICC_READ_Livelihood_and_Gender_Report_2004.English.no_cover.pdf

http://bqqox.small.eu.org/archives/65

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/1-The-Rice-Cassava-Swidden-Cycle-before-1986-and-Present-Day-Note-Data-for-the_fig1_237328774

Related Posts

Trees of Peace from Hiroshima: A Time Traveler and Emissary of Hope

Cinder Cone Chronicles: Lessons from Drought, Data, and Determination