In Search of Understanding

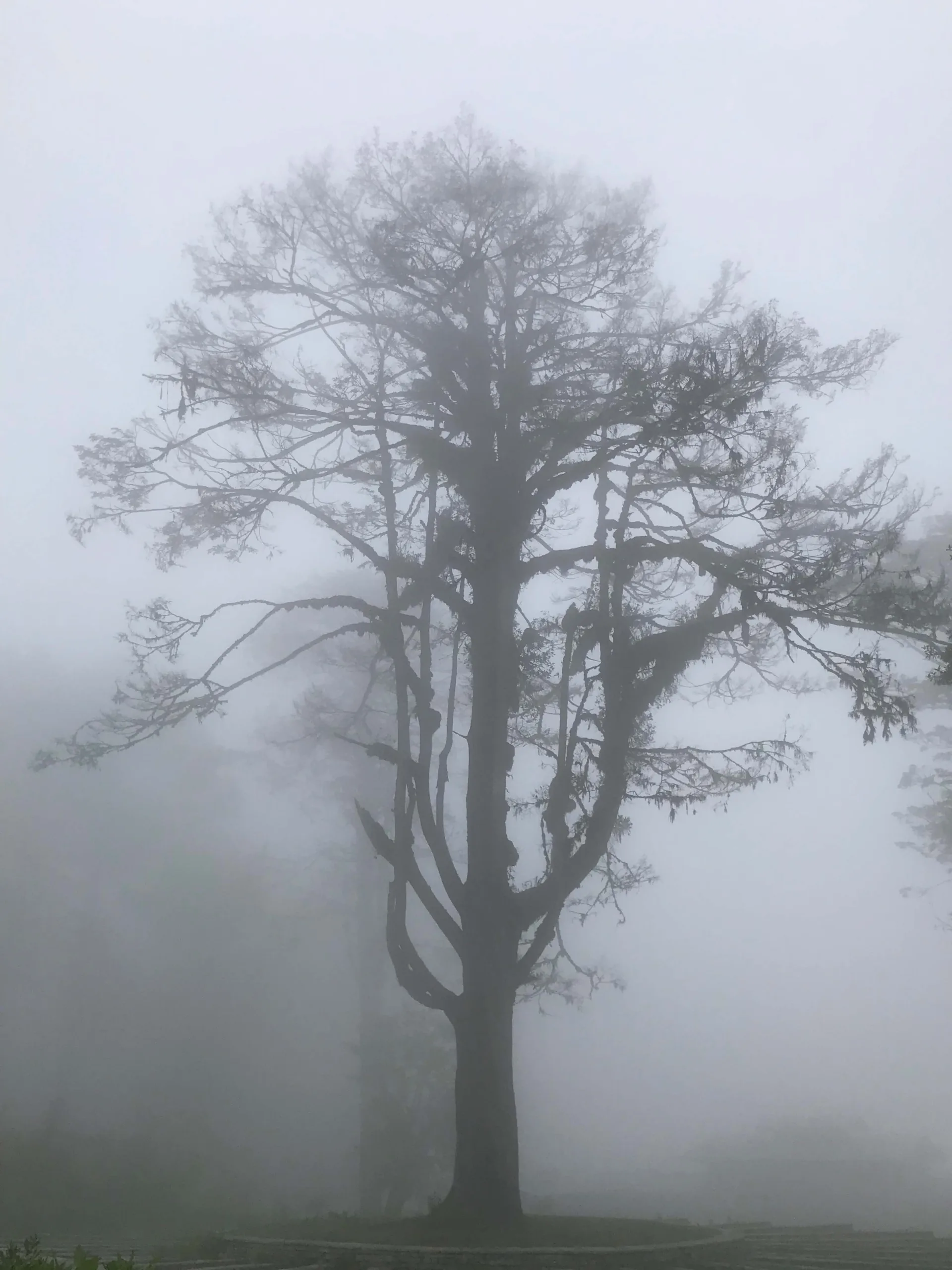

At 7,000 feet above sea level, the sun is intense. So intense that I can feel it slice through me with the perfect aim of a Bhutanese master archer, neatly cutting my body into nothing more than a cloud of infinitely small pieces of universe. The wind that blows off the leaves of the tsenden (Himalayan cypress, Bhutan’s national tree) filters through me and my belly inflates, filled with the song of the grey warbler, the immense energy of the ants and the millions of prayers picked up by the breeze as it brushes gently through the prayer flags sending multitudes of goodwill across the mountains and valleys.

It’s not difficult to see how the media has abstracted this nation to such idealized terms as “the Last Shangri-La” or “the land of happiness.” The landscape seems to have been carefully steeped, at exactly the right temperature, to create a complex and invigorating, yet soothing, brew of culture, spirituality, and timeless organicism. The forested slopes are a pointilist’s dream, each proud tree offering a novel shade of green to a tapestry so rich you wish you could reach out and rub it gently between your fingertips. These natural fabrics would be unparalleled if it were not for the traditional textiles woven by the Bhutanese people, which, as we gently lift them from the densely packed shelves, feel heavy in our arms with time and energy and socio-ecological relationships that reach back into the depths of what it means to be human.

But Bhutan, like any nation, cannot be boiled down, reduced, like a simple cup of tea. It is full of complexities and contradictions: Bhutanese people refuse to kill a fly (based on the Buddhist belief in doing no harm to any sentient being), and yet the traditional cuisine encompasses a variety of well-loved meat-based dishes. Each Bhutanese person is legally a custodian of the natural landscape, and yet if one peers into the river that runs past our center it would not be surprising to find a fermenting discarded packet of imported two-minute noodles. The dress code is modest, and driglam namzha (Bhutanese code of etiquette) is detailed and prescriptive, but explicit phallic imagery is ubiquitous – owing to a legend that deems them symbols of good luck and prosperity. The more we try to unpack the Bhutanese cultural and spiritual beliefs in search of explanation, the more we are left with a sense of “I simply don’t understand.”

Therein, however, lies an important truth: we cannot fully understand an entire culture – not even our own. Culture is woven of threads of time and space and experience, and as new weave is continually added to the weft, the nature of the entirety changes as an intricate pattern emerges. In our six weeks here, we are able to look at a small section and attempt to carefully follow each thread to see where it comes from, where it leads, and what other threads it intersects with – but eventually it gets lost in an inextricable pattern or travels off into the distant horizon of memory or expectation. All that remains is to step back and look at the endless textile as a whole, and accept that there are limits to what we can know; but that with acceptance of incongruity at the detailed level we are able to appreciate the beauty of the entirety.

The wonder of travel is that it gives us the opportunity to both question and accept. If you probe a Bhutanese person on the apparent inconsistencies in their cultural practices, they may have a long and possibly circular string of justifications and connections that lead to only more questions. And yet they will likely not see this as a contradiction – merely a junction in a much larger map of elements of history, society, individuality, spirituality. When we take a moment to think, we realize that the same goes for our own culture, whatever it may be. Having an outsider’s perspective makes these inconsistencies glaringly obvious, and forces us to question our own beliefs; but we also learn to accept that any culture is a maelstrom of dualities and never-ending knowledge networks. If we are able to accept the infinitude of the whole, these do not necessarily have to pose inconsistencies, simply complexities.

So as we journey through our own discovery of Bhutan, I hope we will remember to consider also the journey through the self. Experience fully the intensity of the sunlight, the turmoil of the mountains, the vibrating silence on the pine needles, the jarring of contradiction and misunderstanding, and through it all, seek to find in oneself the harmony of the whole – a whole inclusive of Bhutan, home (wherever that is to each one of us), the burden of our own life experience, and the spirit of all sentient beings.

Related Posts