Rainforest to Reef

What connection does our Centre, situated at 740m above sea level, an hour inland from the coast and surrounded by rainforest, have with the coast and the Great Barrier Reef? This semester students have been exploring these connections when we’ve focused on catchment (or watershed) management and riparian restoration, culminating in a recent day trip to Fitzroy Island on the Great Barrier Reef.

Up here on the Atherton Tablelands, it doesn’t feel very coastal. It is cooler, for a start, and our recreation tends to be focussed on the nearby forests, rivers and lakes unless we make a special effort to go down to Cairns for a day at the beach or a trip to the reef. Yet every minute of every day, the water in the little stream beside our field station begins, with dozens of other tributaries, its flow downhill to Lake Tinaroo. From there it flows into the Barron River, snaking 160km across the Tablelands and eventually down across the Barron Falls and out to the coast just north of Cairns, one of the largest waterways in the Wet Tropics, meeting the coast adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef.

What happens in the hinterland matters for the Great Barrier Reef. Bank erosion, habitat degradation, fertiliser and pesticide runoff, all contribute to sediment and nutrient loads on the reef. For a graphic example of this in catchments to the north and south of us, check out this video. Students learn about these issues with socio-economics faculty Justus Kithiia and efforts to address them were reinforced in a guest lecture by Ian Sinclair, Barron Catchment Coordinator, who emphasised the diverse land-use of our own Barron Catchment, its many down-stream users and the need to “kick as many goals as possible with the one project” when trying to spread the available funding over a long and varied riparian zone. Through projects such as the Green Corridor and Reef Rescue, community members and organisations are involved in bank repair, remnant enhancement and revegetation aimed at improving river and reef health and enhancing wildlife habitat. Similar efforts are underway in the other Wet Tropics catchments, and this semester students and staff have been part of that effort by participating in several community tree plantings adjacent to waterways.

What of our class visit to the Great Barrier Reef? Fitzroy Island, a 45 minute ferry ride from Cairns, provides a fabulous introduction to the dizzying diversity of coral reef life. On their snorkelling adventure students were thrilled with the number and richness of fish species, the vibrant colours in patches of coral and, for some lucky folk, an encounter with a green sea turtle. However, Fitzroy Island, a continental island in near proximity to Cairns and highly popular with visitors and locals alike, is a microcosm of coastal and reef issues where, unfortunately, pressures on the reef and marine life are very evident.

Our day started with a visit to the Cairns Turtle Rehabilitation Centre facility on the island. here we were introduced to Ella, a green sea turtle who was the victim of boat strike, and learned of the effects that sedimentation can have on sea turtles’ main food source, seagrass beds. Guest lecturer Alastair Freeman, from the Threatened Species Unit of Queensland Environment & Heritage protection agency, then filled us in on other threats to sea turtles such as pig predation of eggs, marine debris, climate change, and the fraught issue of indigenous hunting.

The turtle rehabilitation facility is housed on land provided by the Fitzroy Island Resort. The resort runs tours to the facility for its guests and this helps fund the turtle rehabilitation work. Like any resort, the Fitzroy Island Resort offers accommodation and activities and has substantial infrastructure on the foreshore of the island that is otherwise National Park. Faculty member Justus Kithiia pointed out the challenges of multiple uses in the coastal zone that Fitzroy Island illustrates. As we explored the island’s walking tracks, away from the activity of the resort and foreshore, some of these challenges were evident. How, for instance, could a traditional burning regime be reinstated on the island in such close proximity to a tourism facility? When we contemplate the multiple uses of the reef, the challenge is even greater. How, as Justus Kithiia questioned, do you divide up the sea?

Historically, Fitzroy Island is no stranger to multiple uses. It is part of the traditional country of the Gunggandji people, whose stories tell of a time when, around 6,000 years ago, in a time of lower seas level, Fitzroy was part of the mainland. After European colonisation, it became an important site for the pearling and beche-de-mer industries, was at one time a quarantine station for Chinese miners making their way to the Palmer River Goldfields, and in the 1800s, part of the Yarrabah Aboriginal Mission when it was used extensively for gardens. Many Mandingalby Yidinji people, whose country near Yarrabah we visit, have traditional or historic ties with Fitzroy Island. During WW2, Fitzroy Island was a radar station which, along with gun emplacements on the mainland at Cape Grafton, served to protect the Grafton Passage. Now, it is a popular visitor destination and a prominent part of Great Barrier Reef tourism out of Cairns.

So, having learned a bit about sea turtles, the island, coastal zone and reef issues, we did what nearly every other visitor to Fitzroy does – headed for the water. I’ve been lucky enough to snorkel at several different places on the Great Barrier Reef but still get a thrill when I first look under the water and find myself in another realm, surrounded by colourful marine life. This time was no different and for a while I meandered along, following a huge “bait ball” of schooling fish, absorbed in their movements and behaviours.

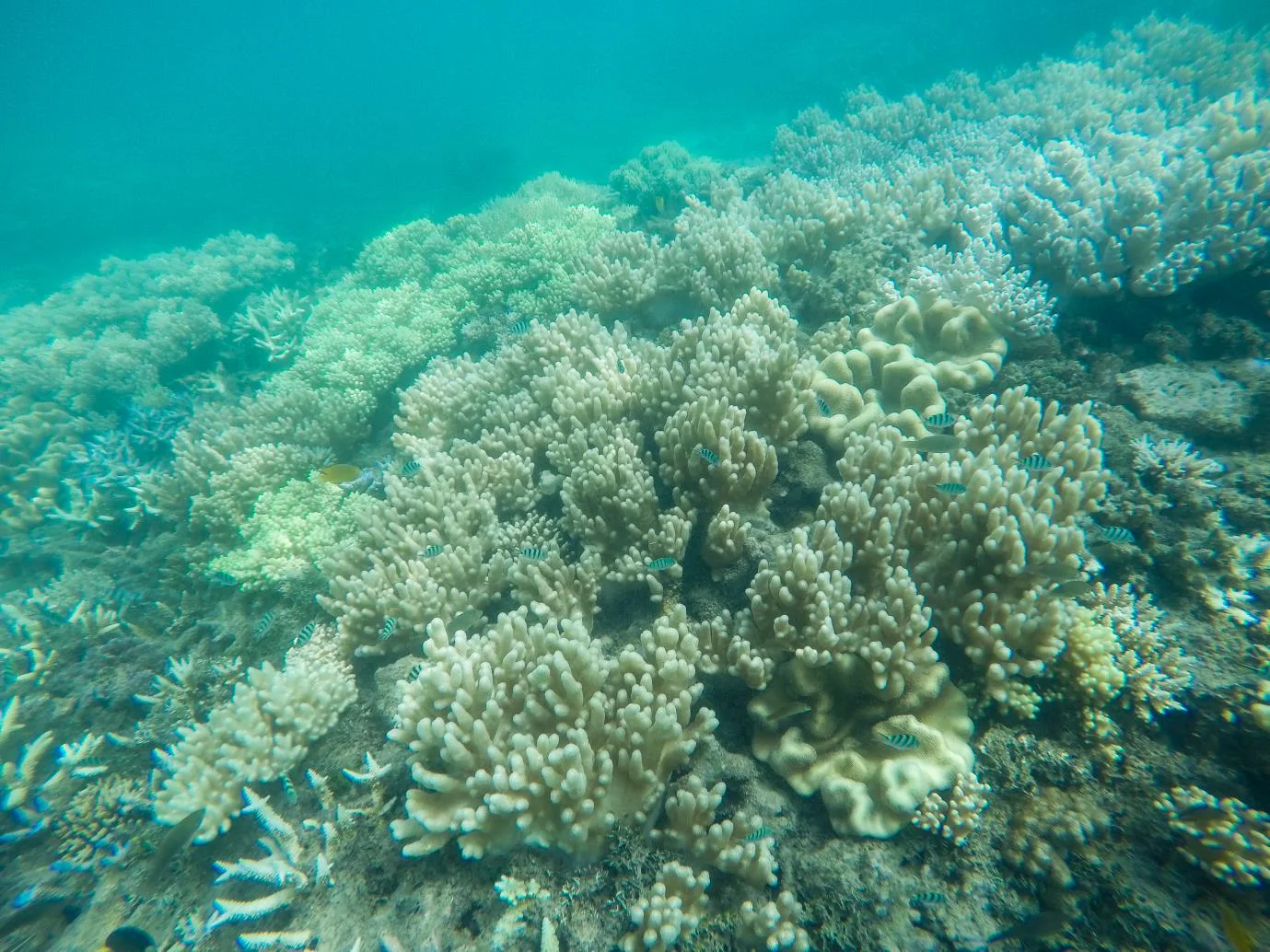

As I moved from one part of the fringing reef to another, however, something else captured my attention. Why is that large patch of coral looking so pale, I wondered? Gradually it dawned on me – I was seeing coral bleaching; a whitening effect that occurs due to stress-induced expulsion of the coral’s symbiotic algae. This is usually related to long periods of higher than normal water temperatures, as currently being experienced across the Great Barrier Reef. Other stressors may also be involved, such as high nutrient and suspended sediment loads and toxicants like pesticides.

Coral can recover from bleaching, but local water quality plays a large part in its ability to do so. This brings me back to our little stream and the epic journey of its water from rainforest to reef, via the multitude of agricultural and domestic uses on the Atherton Tablelands. I hope the amelioration efforts being made in the Barron Catchment, and in all catchments flowing into the Great Barrier Reef, aren’t too little, too late, for the pretty fringing reefs of Fitzroy Island and beyond.

Photos by Lucy Portman

Related Posts

Cinder Cone Chronicles: Lessons from Drought, Data, and Determination