Naming the Creatures

We went to the temple complex of Angkor today, not for its temples but for the wild creatures that can be found in its remaining patches of forest. We walked slowly along a forest trail on an ancient wall, bearing binoculars, wildlife sightings journals and a picnic breakfast, and we looked at things — stingless wasps, red weaver ants, coppersmith barbets, Asian paradise-flycatchers, a white-rumped shama. Identifying wildlife in the field is a small component of the Ecosystems and Livelihoods class. At times I think it is the most valuable thing we do.

At one point, after a minute of staring up into a towering diptocarp tree with three large black and white birds bouncing on its branches, one of our students asked, “Was that George?” George is an oriental pied hornbill who lives at the Angkor Centre for Conservation and Biodiversity’s wildlife rehabilitation center. The students met George at the beginning of their second week in Cambodia. Now, two weeks later, they have seen his cousins in the wild.

When I told the students that part of their course would require them to identify wildlife, mainly birds, I said these words: Some of you will love this assignment, others will endure it. Some of you may find yourselves somehow becoming birders after the fact. It has happened to others before you. But whether or not identifying wildlife is part of your future, this is an exercise in being attentive — of seeing the world, and then finding knowledge of what it is we see. This requires honing the skill of paying attention to the world around us — of being attuned, of noticing what flies by. It requires remaining attentive and aware of the present moment.

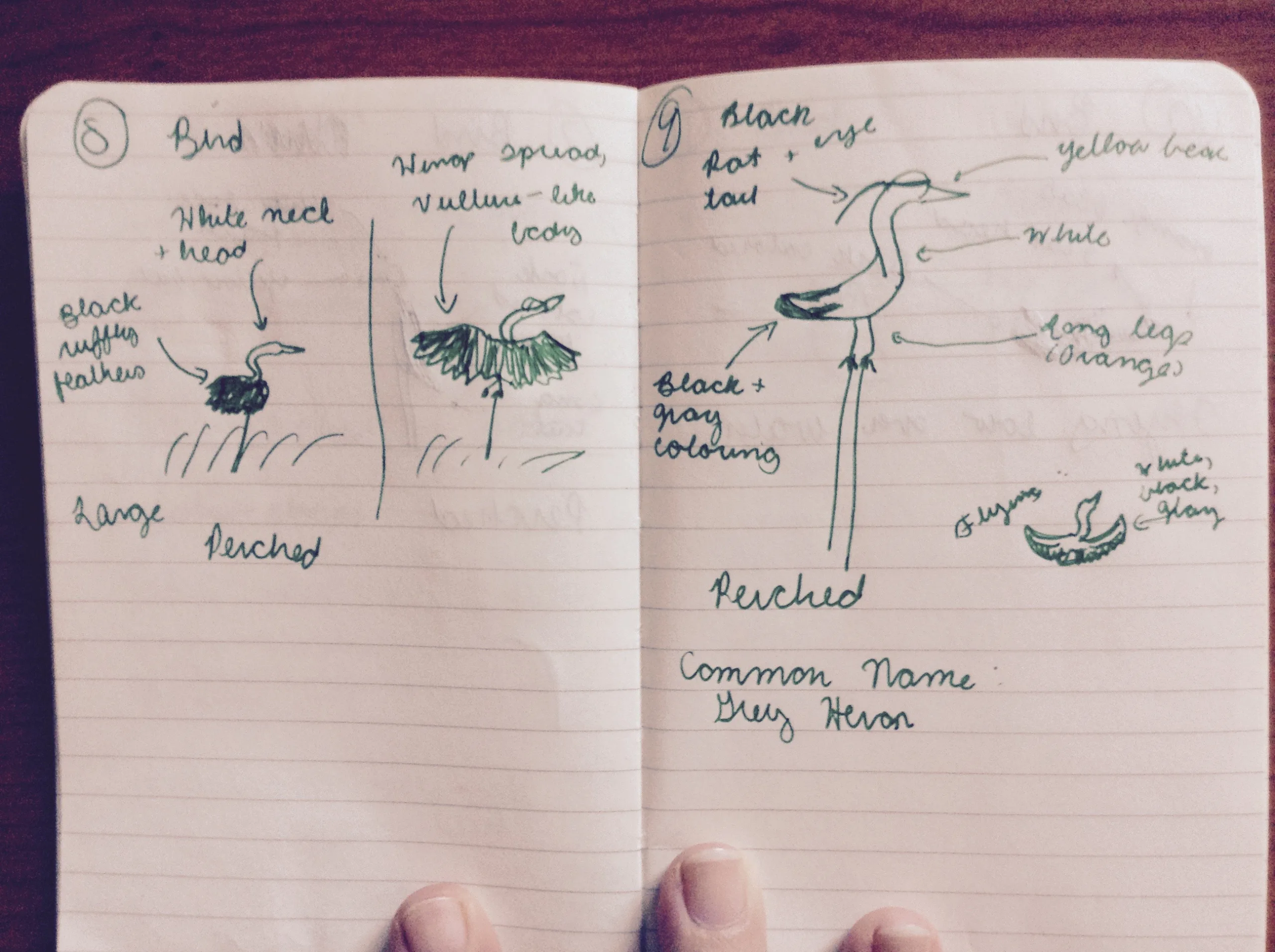

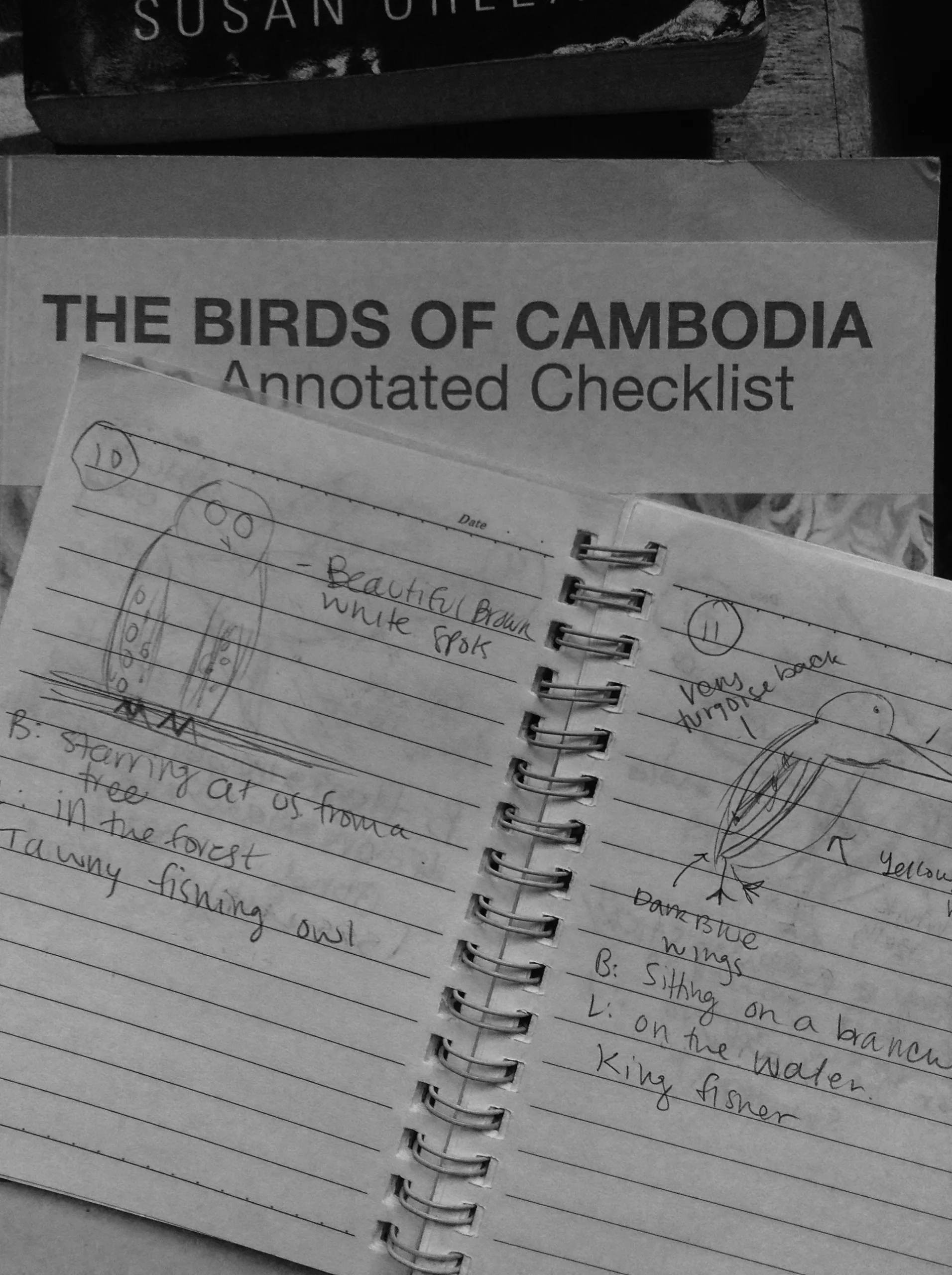

This is part of what we do here at the SFS Center for Mekong Studies. We walk along forest trails, looking and listening for the creatures that cross our paths — the birds in the trees, the lizards in the fallen leaves, the squirrels dashing along the branches over our heads, the spiders hanging in stately silence upon their webs. And when they happen along, we take out our wildlife journals and write them down — describing their appearance, their behavior, and their habitat.

A student of nature does not need to sketch well in order to practice morphology, the study of the forms of things. They just need to be able to record what they see: does the creature have fur? feathers? scales? bars on its tail? did its tail wag? did it spear a fish with its beak? did it turn somersaults in the air? They need to be able to look closely enough, and describe something well enough, that later, when the field guides are open and they consult their notes, they can find and name that wild creature.

And why does such naming, such taxonomy, matter? Carol Kaesuk Yoon put it well in her 2009 essay, “Reviving the lost art of naming the world”:

Today few people are proficient in the ordering and naming of life. … We are, all of us, abandoning taxonomy… Even when scads of insistent wildlife appear with a flourish right in front of us, and there is such life always — hawks migrating over the parking lot, great colorful moths banging up against the window at night — we barely seem to notice. We are so disconnected from the living world that we can live in the midst of a mass extinction, of the rapid invasion everywhere of new and noxious species, entirely unaware that anything is happening. Happily, changing all this turns out to be easy. Just find an organism, any organism, small, large, gaudy, subtle — anywhere, and they are everywhere — and get a sense of it, its shape, color, size, feel, smell, sound. Then find a name for it. … To do so is to change everything, including yourself. Because once you start noticing organisms, once you have a name for particular beasts, birds and flowers, you can’t help seeing life and the order in it, just where it has always been, all around you.

We care more about the things we are attentive to. The true goal of all these hastily scrawled journals is a greater appreciation of the diversity of the non-human creatures with which we share our world. The hope is that the greater our knowledge, the greater our mindfulness.

Some days that looks like a student asking after a brief flurry of observed motion, “Was that a squirrel? Snap!,” followed by urgent scribbling in their wildlife journal. Some days it looks like a student alight with happiness after seeing a mousedeer scurry across the path. Some days it looks like a collective sigh of happiness at seeing another George. However it looks, it matters, and that is why we learn to name the creatures.

Related Posts

Alumni Reflections: Stories of the Return to Kenya